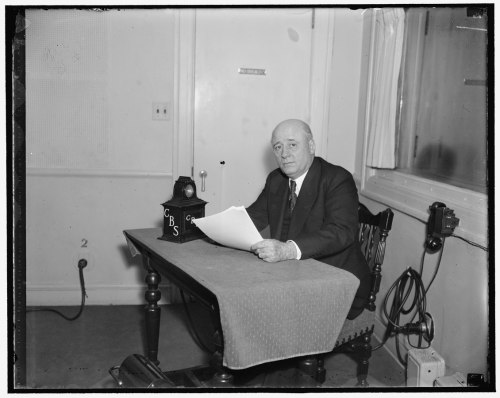

Mr. Speaker, Mr. Sam

Working and Learning

Born in 1887 in Tennessee, Sam Rayburn grew up on a cotton farm in Bonham, Texas. At 18, he attended East Texas Normal School, completing his degree in two years while also teaching school to earn the money to pay for his college. He taught for a couple of years after graduating before pursuing a different dream: law and politics. At only 24, Rayburn was elected to the Texas House of Representatives in 1906. While serving in the legislature, Rayburn also attended the Law School at the University of Texas, passing the bar in 1908.

Speaker of the Texas House

In 1911, Rayburn

narrowly won election as Speaker of the Texas House of Representatives.

One of his first moves was request the appointment of a special

committee to determine the “duties and rights of the speaker.”

As it turned out, the Speaker had enormous power which had gone largely

untapped. Rayburn used this power to preside over a well-run

progressive session. This would not be Rayburn’s last term as Speaker,

though the next would require a change of scenery.

The National Stage

In 1912, Rayburn won election as a Democrat to the Fourth Texas District of the US House, where he would serve for the next 49 years. Rayburn was assisted by another powerful Texan, John Nance Garner, who helped Rayburn make connections and get appointed to powerful committees. In 1937, he became the Democratic Majority Leader, then, in 1940, he became Speaker of the US House of Representatives, a position he retained, except for a few interruptions for Republican controlled sessions, until his death. Almost immediately, Rayburn proved his leadership, helping Roosevelt keep the US Military intact on the eve of World War II, when isolationists would have let it lapse. He would go on to be key in obtaining funding and keeping secrecy for the Manhattan Project. After the war, Rayburn would continue to be a giant in the House, often collaborating with fellow Texan, Senator Lyndon Baines Johnson, to muscle legislation through Congress, including one of the first civil rights bills.

Mr. Sam

Rayburn was personable, preferring private meetings to public confrontations, and kept a middle-of-the-road stance during several polarizing times. He was known for being un-bribable, refusing any donations larger that $25. When Republicans gained control of Congress in 1947, Rayburn lost the use of the car provided for the Speaker. To show their appreciation, 142 Democratic congressmen and 50 Republican congressmen pooled $25 checks to purchase him a new car. Rayburn accepted the car, but returned the checks from the Republican congressmen, since he felt it would be a conflict of interest as he was continuing to serve as Democratic Minority Leader. Rayburn came into the legislature when Wilson was president and died in 1961 during the Kennedy administration. Altogether, Rayburn served 17 years as the Speaker of the House, a record that has yet to be broken. In Washington, D.C. and throughout Texas, people fondly remember “Mr. Sam.”