School, War, and Law

Beauford Jester was born into a political family: his father had been lieutenant governor under Governor Culberson. Following in the tradition, Jester attended Harvard Law School, but put his studies on hold to serve in World War I as a captain in the Army. When the war ended, he returned to his studies at the University of Texas. He earned his law degree in 1920 and returned to Corsicana to start a practice and help run the family ranch. Jester served on the UT Board of Regents and, in 1933, became the youngest chair of that board. He undertook a massive building campaign, giving the UT campus many of its iconic buildings, including the UT Tower.

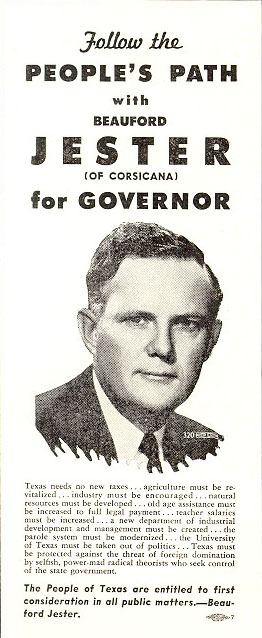

Politics

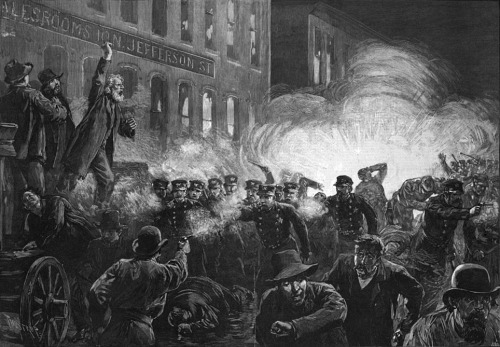

In 1942, Jester was appointed to the Railroad Commission, a position he kept in the next election. From there, Jester campaigned for governor in the 1946 election. There was a wide field, but he won the Democratic primary and then the state election. Jester’s two terms saw a few milestones in Texas history, including the first budget over $1 million. He worked for increased funding for education, rural roads, and state parks. Jester supported anti-lynching measures and a repeal of the state poll tax, though he opposed civil rights legislation on the national level. He also supported making Texas a right-to-work state, preventing union dues from being deducted automatically from paychecks, and prohibiting mass picketing, all of which earned him a reputation as anti-union.

A Fateful Train Ride

A few months into his second term in office, Jester took the train from Austin to Houston to take advantage a vacation after the legislative session and complete what he called a “secret mission.” It had been a hectic session, with members of the legislature calling for Jester’s impeachment and Jester threatening a special session. Jester was supposed to stop at a Galveston clinic for a physical, something he needed after the stress of the session. He would never make it to his appointment. Sometime after leaving Austin late on the night of July 10th, Jester suffered a heart attack and died, presumably in his sleep. Despite traveling with several state troopers as bodyguards, Jester’s death wasn’t discovered until a porter attempted to wake him at the train’s arrival in Houston.

Jester’s body was flown back to Austin, where a short funeral service was held in the Senate Chamber. It was then taken back to his home town of Corsicana where he was buried. Jester was succeeded as governor by a man with perhaps one of the most appropriate last names, Allan Shivers.