More than a Farmer

Best known as the father of Lyndon Baines Johnson, Samuel Ealy Johnson, Jr. served as an inspiration and spring board for his son’s career. Johnson was born in Buda, Texas, but moved to the Hill Country at a young age. He desperately wanted to go to school and become more than a farmer, but the schools in the Hill Country required tuition fees and his family was poor. To help pay for school, Johnson bought a barber’s chair and tools and gave hair cuts in the evenings. Even so, he had to leave school before he graduated. Even without his diploma, Johnson studied diligently and was able to pass the examination for a teacher’s certificate. He spent the next several years teaching in one room school house around the Hill Country. Eventually, finances forced him to move back to the family farm, which he took over when his father retired.

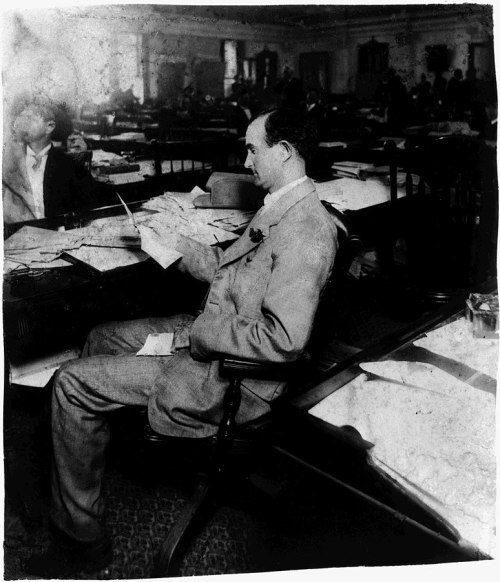

House of Representatives

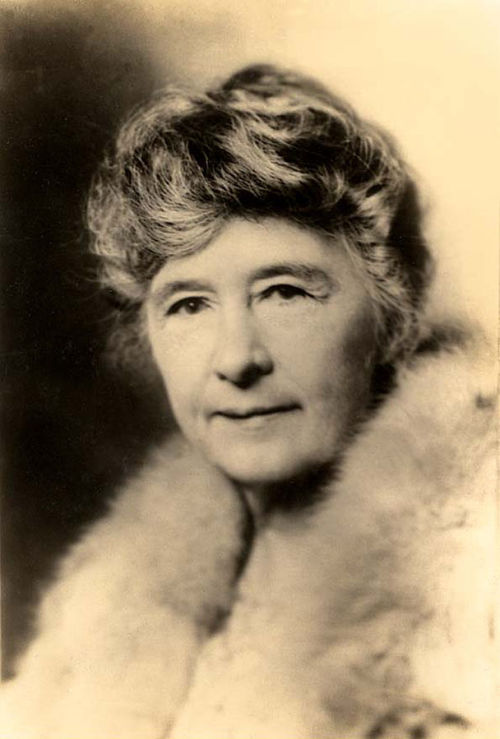

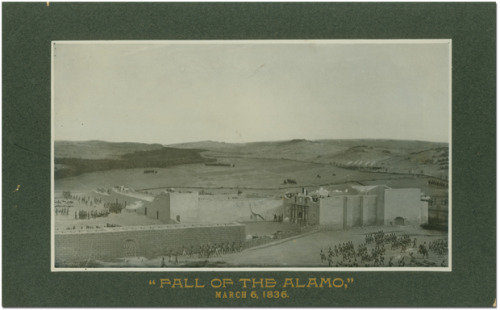

In 1904, financially solvent from a few good years on the farm and with a popular reputation in the Hill Country, Johnson ran for and won a seat in the Texas House of Representatives. During his first two terms in the House, he worked to regulate business and pushed through a bill providing state funding to reimburse Clara Driscoll for the purchase of the Alamo property and provide for its preservation. Johnson met Rebekah Baines while she was working as a reporter of the legislative session and the two married in 1907. Funnily enough, Baines was the daughter of Joseph Wilson Baines, whose seat Johnson had taken over.

Boom and Bust

In 1909, Johnson was again facing hard financial times and retired from the legislature. Though many legislators found jobs in industries or lobbying after their terms, Johnson had always steadfastly refused bribes and fought against the interests of big business, so he returned to the family farm. After many years of poverty and five kids, Johnson was slowly able to put the family back onto stable footing. He began buying real estate and then businesses around Johnson City. In 1917, a special election was held for Johnson’s old seat in the House and he ran unopposed. He would hold the seat until 1923, despite, once again, losing almost everything investing in the cotton market. This cycle of boom and bust was difficult for the family and particularly for Rebekah. She did her best to instill stability and the love of education and culture in her children, which Lyndon Johnson credited as a driving force in his life. Johnson suffered a series of heart attacks in the mid 1930s and passed away in 1937, the same year his son won a seat in the US House of Representatives.