Lead Up to the Battle

The Texas Revolution began with a bang, but not much of a battle. In 1831, the Mexican army had loaned the townspeople of Gonzales a cannon to protect themselves against Native Americans. It wasn’t much, just a foot long signal cannon, but the townspeople came to think of it as their own, despite agreeing to give it back if ever the Mexican army asked for it. In 1835, Northern Mexico and the Yucatan revolted against President Santa Anna, who had suspended the 1824 Constitution and declared himself president for life. Colonel Ugartechea, stationed in San Antonio de Bexár (modern San Antonio, Texas), saw the whole situation and thought that he should retrieve the cannon, just in case the townspeople decided to join in the general revolt. In September of 1835, he sent a few men to request the return of the cannon. The alcalde refused and sent the men back empty handed. Ugartechea decided stronger measures were needed and, on September 27th, 100 dragoons left San Antonio de Bexár bound for Gonzales.

All Over But the Shooting

The townspeople of Gonzales had buried the cannon after they had sent Ugartechea’s men packing, but as word came of the approaching dragoons, they hurriedly dug it up and mounted it on a wooden carriage. The dragoons arrived near Gonzales on the 29th, but the townspeople sent 18 men to block the nearest river crossing. They told the soldiers that the alcalde was away and they would have to wait until he returned, so the soldiers made camp on the far side of the river. Meanwhile, the townspeople called for reinforcements and were able to gather about 150 men. John Henry Moore was elected commander of the hastily assembled militia. On October 1st, a Coushatta scout told the Mexican commander, Castañeda, that the men were gathering and he decided to move his men further up the river to try to find another place to cross. That night the Texans crossed the river and headed north to the Mexican camp. On the morning of October 2nd, they fired the cannon at the Mexican soldiers, who quickly retreated. Castañeda asked for a parley and the Texans, though initially suspicious, agreed. Moore explained that they were not loyal to Santa Anna’s dictatorship, but rather to the Constitution of 1824. Castañeda expressed his sympathies for their position but, despite the Texans’ offer for him to join them, said that he was honor-bound to carry out his orders. The commanders returned to their camps as the Texans hoisted a flag bearing a star and cannon on a white background with the words “Come and Take It” underneath. The Texans again fired on the Mexican troops and Castañeda quickly retreated, telling Ugartechea, “since the orders from your Lordship were for me to withdraw without compromising the honor of Mexican arms, I did so.” The Texas Revolution, not yet a war for independence, had begun.

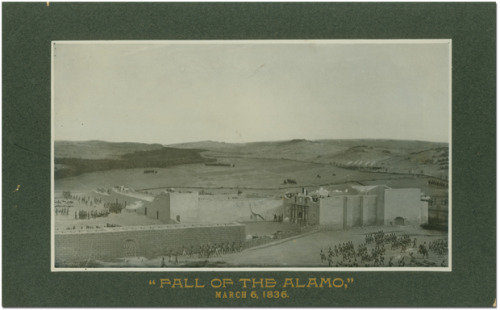

The Come and Take It Cannon

The cannon that had sparked the revolution was taken on to Goliad, and then moved with the army on its march to San Antonio de Bexár, but its fate is uncertain. One report says that the cannon’s cart couldn’t keep up with the army on the march to San Antonio and it was abandoned, buried along the banks of a creek near Gonzales. In 1936 (conveniently, during the Texas Centennial), a cannon was unearth after a flood. The Smithsonian confirmed that the cannon had been buried for an extended time and was of a type of small swivel cannon that was common in 1836. That cannon is now in a museum in Gonzales. However, other historians claim that the cannon was taken to the Alamo and captured by the Mexican army after its fall. Then, it was melted down with the other cannons when the Mexican army retreated. Though it was only fired twice at the battle of Gonzales, and its location is uncertain, the Come and Take It Cannon will continue to loom large in the Texan imagination.