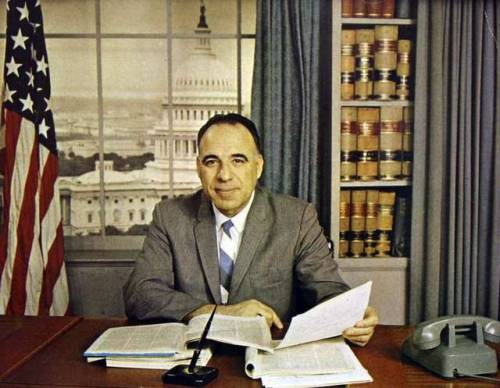

Martín and Patricia

Martín de León was born to a wealthy family in what is now Tamaulipas in 1765. Though his family usually educated their children in Europe, Martín decided not to go. Instead, he became a merchant and then joined the army. Because he was born in New Spain, he couldn’t rise above the rank of Captain. In 1795, he married Patricia de la Garza, the daughter of the Commandant of the Eastern Internal Provinces, a woman 10 years his junior. The couple settled in Tamaulipas and began ranching.

Ranching and Resistance

In 1805, Martín took a trip north to several cities in Tejas and decided to move the family ranch up to the area north of present day Corpus Christi on the Aransas River. The cattle were branded with the de León brand, EJ for Espirtu de Jesus. The brand was registered in 1807, the first cattle brand in Texas. Martín quickly became interested in creating a colony in the area, but his repeated requests were denied by the Spanish government, which questioned his loyalty, with good reason, as it turned out. The De León family sided with the Republicans during the Mexican War for Independence. The family spent most of the war in San Antonio, but returned to their ranch in 1816, as hostilities on the frontier died down. In 1823, Martín purchased cattle in New Orleans and drove then to Texas, adding them to the 5,000 head of cattle the family already owned.

Empresario

Martín had not given up on his idea of establishing a colony in Texas. In 1824, he petitioned the provincial government for permission to settle 41 families on and found a town on the Guadalupe River. His contract was approved, and since he was a Mexican citizen, he had almost no restrictions and several benefits, including exempting his colonists from taxes and duties for seven years. Patricia contributed $9,800, as well as cows, mules and horses that she had inherited from her father. The De León family arrived at the town site late in 1824 along with a few other families, and the rest joined them the following spring. The town was called Nuestra Señora de Guadalupe de Jesús Victoria and the colony was named Guadalupe Victoria, after the first president of Mexico. Each family received a plot in town, a league – 4,228 acres- of grazing land and a labor – 177 acres – of arable land. While Martín set up the land, Patricia focused on the culture. She founded a school and a church, donating funds as well as furniture and other items. Though their house was rough, with dirt floors, Patricia brought beautiful furnishings from Mexico. The De León colony was the only predominantly Mexican colony in Texas, though it also included American and Irish families. Because the borders of the De León colony were undefined, they came into frequent conflict with surrounding colonies, especially the DeWitt colony. In 1829, Martín got permission to bring 150 more families and expand the colony, which brought more conflict with the DeWitt colony. However, in 1831, DeWitt’s grant expired and the De León colony was able to expand into the vacant land. By 1833, when Martín died in a Cholera epidemic, the colony had given out more than 100 titles, making the De León family the only empresarios in Texas other than Stephen F. Austin to fulfill their grant.

Revolution and Heartache

Even without their patriarch, the De León family were ardent supporters of the Texas Revolution. Two son-in-laws served in the Texas army and much of the rest of the family contributed horses, mules, and supplies. Because of their support, the family was targeted by General Urrea when he occupied the area and two of Patricia’s sons, Fernando and Silvestre, were arrested. Despite their support, the time after the Texas Revolution was not an easy one for Tejanos. The youngest De León son was murdered by cattle rustlers and the family was forced to flee to Louisiana. They later moved to Tamaulipas, Patricia’s childhood home and Patricia sold some of the family’s land to help make ends meet. In 1844, Patricia returned to Victoria, only to find her fine furnishings spread among the newcomers. Despite the lack of welcome, Patricia spent the rest of her life in Victoria devoted to the community, particularly the church. When she died, Patricia donated her homestead to the Catholic Church. Today, St. Mary’s Church stands on the site.